“Specie Jars + Speedy Oil” (Part Two of a talk given to the Medical History Society in 2006)

I continue tonight from the position of Uncontrolled Dispensing which I covered in my talk last year. Pharmacy 1880 Onwards takes us on the journey into the period of my grandfather’s practice, he being registered in 1909.

From the introduction of Pharmacy Act in 1880 the profession became totally regulated through registrations, effectively disenabling all unqualified and unprofessional individuals to practice pharmacy dispensing.

The late Victorian period was still very traditional, with preparation of medicines being mostly manual. There was still the use of folded powder papers; the hand rolling, rounding and coating of pills; and the labour intensive method of hand making suppositories in metal moulds. However, changes were happening.

1879 saw the invention and patenting of the Limousin Cachet machine, whereby a bulk run of cachets could be made at once by the pharmacist. The fast mechanised production of tablets was presented to the world by Henry Welcome in 1884. Of a similar period, 1875, Parke Davis and Company developed and patented the gelatine capsule. Furthermore through the mid-19th century research and development on alkaloids was advancing, and, mass production now began by large industrial concerns, of strychnine; quinine; morphine etc.

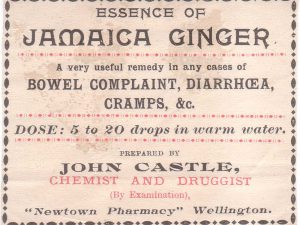

The advent of this new mass-market approach led to the global advertising and promotion of these items, making popular many of the well-known proprietary brands of company’s products that we use today. The pharmacist’s often inability to maintain a consistent quality, as well as the manufacturing complexity of these medicines meant that the retail pharmacist’s own manufactory base was beginning to shrink. However, New Zealanders were not seen slow in moving into home grown manufacturing also.

George Bonnington had a sizeable 3 storey manufacturing facility near Ferrymead, Christchurch, the building, with faint signing writing, still survives. We also had a sizeable component of rural chemists dispensing veterinary products, and A.E. Sykes, a New Plymouth pharmacist around the turn of last century, manufactured and wholesaled through stock merchants throughout New Zealand. Product lines included drench; udder ointment and Abortion cure. Photos of shop interiors of this period and onwards show the plethora of advertised pre-made proprietary branded items. You could even obtain a 15” x 24” 10 coloured lithograph of “Granny” Chamberlain for your window, from a Sydney company promoting a cough remedy.

George Bonnington had a sizeable 3 storey manufacturing facility near Ferrymead, Christchurch, the building, with faint signing writing, still survives. We also had a sizeable component of rural chemists dispensing veterinary products, and A.E. Sykes, a New Plymouth pharmacist around the turn of last century, manufactured and wholesaled through stock merchants throughout New Zealand. Product lines included drench; udder ointment and Abortion cure. Photos of shop interiors of this period and onwards show the plethora of advertised pre-made proprietary branded items. You could even obtain a 15” x 24” 10 coloured lithograph of “Granny” Chamberlain for your window, from a Sydney company promoting a cough remedy.

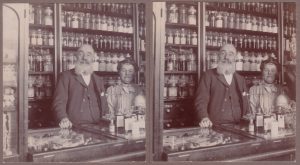

The late Victorian pharmacists were now a skilful and adaptable group, generally with established shops furnished with quality dark wood fittings (either imported mahogany or dark-stained native kauri). Mirrors, pear-shaped coloured carboys and highly painted luxurious specie jars abounded, showing a true sense of pomp and grandeur; leaving a feeling of awe and confidence with the customer.

The late Victorian pharmacists were now a skilful and adaptable group, generally with established shops furnished with quality dark wood fittings (either imported mahogany or dark-stained native kauri). Mirrors, pear-shaped coloured carboys and highly painted luxurious specie jars abounded, showing a true sense of pomp and grandeur; leaving a feeling of awe and confidence with the customer.

One entrepreneurial Englishman arrived in NZ with his cabinetry skills, making up to 6 sets of solid mahogany pharmacy shop interior fittings, one such set still survives from Greens Pharmacy, (formerly in Dixon St, Wellington.)

Local Trade journals were published, one initiated by the large trade house Sharlands (which publication was later taken over by the NZ Pharmacy Assoc.). Also “The Chemist, Druggist and Pharmacist of Australasia”, established in 1886, which created a wonderful monthly information flow between the two colonies, and “The Home Country”.

This was also the period which began the plethora of glassware items that could be embossed with the chemists name and location, and either sold or given away, most being made by Whittal Tatum, USA, which have now become very collectable. Apart from medicines, pharmacies stocked an immense range and volume of other items, including Baby Feeders( often customised with the shop’s own name;) Turkish Sponges; men’s shaving gear; ceramic pap dishes and feeder cups etc.

However, they couldn’t sell enough, and Mr. Gillman of Onehunga was among the first of his profession in Auckland to have regard to the need to keep abreast of the times. Consequently, when he observed from the reading of overseas journals that chemists and druggists were stocking their premises with goods that hereto were considered outside the province of such a business he was not slow to follow suit. He not only imported new and improved drugs, but also introduced hot-water bottles, teething powders, toothpastes and photographic accessories. In 1895, for the better extraction of teeth, he imported for his own use, a set of dental instruments of a newly designed type, which were coming into general use in England and America.

However, they couldn’t sell enough, and Mr. Gillman of Onehunga was among the first of his profession in Auckland to have regard to the need to keep abreast of the times. Consequently, when he observed from the reading of overseas journals that chemists and druggists were stocking their premises with goods that hereto were considered outside the province of such a business he was not slow to follow suit. He not only imported new and improved drugs, but also introduced hot-water bottles, teething powders, toothpastes and photographic accessories. In 1895, for the better extraction of teeth, he imported for his own use, a set of dental instruments of a newly designed type, which were coming into general use in England and America.

Naturally, many of his fellow-chemists in Auckland were apprehensive lest the standards of their profession would be lowered if they followed Mr. Gillman’s example. But he counted the objections by pointing out that grocers were stocking proprietary medicines, cough lozenges, throat tablets and the like, and in this way were making deep inroads into the fields previously regarded as being reserved for chemists and druggists. The lead he gave was soon adopted generally throughout New Zealand.

Naturally, many of his fellow-chemists in Auckland were apprehensive lest the standards of their profession would be lowered if they followed Mr. Gillman’s example. But he counted the objections by pointing out that grocers were stocking proprietary medicines, cough lozenges, throat tablets and the like, and in this way were making deep inroads into the fields previously regarded as being reserved for chemists and druggists. The lead he gave was soon adopted generally throughout New Zealand.

Dentistry, often crudely and basically administered when out of the larger urban areas, was not uncommonly undertaken on a default basis by the country pharmacist. This was certainly so in the shop my grandfather managed in Mania, South Taranaki in 1917. My father recorded the following dubious practice and public spectacle of tooth extraction. To quote;

“In the shop was an amazing range of appliances for the use of the chemist, with a complete dentist’s armoury which was in steady use, and Dad had a large clientele of Maori men. After a few times wrestling with great big teeth Dad had a rule that all patients must bring with them two big assistants. It must be remembered that anything out of the ordinary was public property and tooth pulling was good fun.

The procedure was that a special lounge chair with arms was used for the patient, then one assistant would hold the patient’s head firmly, and the other assistant would extract the tooth under Dad’s guidance. I was always in the front of the audience, as it was my father’s shop. The most memorable was when a large Maori came in for an extraction with his two assistants. Dad was a very small man with poor physique, so wrestling out this large molar was quite beyond his ability. In any case, everybody enjoyed the performance except, I suppose, the patient.

This particular day the patient was readied and the operator given the forceps and shown the offending tooth. With much wrestling, twisting, grunting and groaning, out came the tooth. Dad took one look at it and said that it was a good tooth. The operator merely smiled and went in again, this time he got the right one. The patient never said anything, spat a huge gob of blood on the floor, everybody applauded, and the bill was paid and off they went, no threat of legal proceedings for malpractice then”.

This particular day the patient was readied and the operator given the forceps and shown the offending tooth. With much wrestling, twisting, grunting and groaning, out came the tooth. Dad took one look at it and said that it was a good tooth. The operator merely smiled and went in again, this time he got the right one. The patient never said anything, spat a huge gob of blood on the floor, everybody applauded, and the bill was paid and off they went, no threat of legal proceedings for malpractice then”.

Another area of business embraced by a handful of Pharmacists was the establishment of the American Soda Fountains. As quoted in 1912 Australasian trade journal.

“Mr. W. R. Cook, who returned recently from his quick trip to the United States, has been fitting up a very stylish and up to-date soda fountain in the shop next to his own in High Street, Christchurch. He is also supervising the fittout of the two shops in Auckland to be opened in Queen Street, in conjunction with the company, which was successfully floated to take over his various businesses. Mr. Cooke left to personally take charge of the Auckland shops at the end of September. The new soda fountain is on the Lippnocott model, which is as nearly automatic as possible. The shop fitted with the soda fountain is quite distinct from the drug section of the business. Mirror backs and many artistic stools and tables for the use of patrons have helped to attract the public, largely now that the warm weather has begun”.

We should remember here that the proliferation of Coca-Cola to the world, had its humble beginning as a tonic in a chemist shop in Atlanta. The soda fountains had a huge popularity and success through the Prohibition period in the U.S.A. The astute retailer didn’t miss the opportunity to market their products, and in the 1915 Australasian Trade journal a “hint” was given to install “shallow glass table cases for serving the drinks, said to produce a prompt increase in sales of perfumery and toilet articles…women sitting for their drink naturally look at the goods displayed…”

Not all shops were fitted out in the style and high quality I have mentioned above. In the 1920’s period the original owner of Remuera Pharmacy, Mr F.G. Blott kept a very lean stock level. If a person requested an item he didn’t have in stock, he would tell the customer to come back later in the day when he’d prepared it, then phone Kempthorne Prosser (the supplier in central Auckland) and have them put it onto the Remuera tram, and it would be delivered to the shop by the tram motorman.

Not all shops were fitted out in the style and high quality I have mentioned above. In the 1920’s period the original owner of Remuera Pharmacy, Mr F.G. Blott kept a very lean stock level. If a person requested an item he didn’t have in stock, he would tell the customer to come back later in the day when he’d prepared it, then phone Kempthorne Prosser (the supplier in central Auckland) and have them put it onto the Remuera tram, and it would be delivered to the shop by the tram motorman.

During WWI an irreversible change occurred in the staffing of the Chemist shop: Formerly a male preserve, now we had “The Exit of the Male Assistant and the Entrance of Girl Cheap Labour”, quoted the Chemist and Druggist magazine. “The masters have discovered that girls can do the work for 1/ 6th of the pay, and naturally they are employing the cheaper labour, _ _ _. Girls are taking the male-assistant places. _ _ _ “7 in one shop, 4 in another, 3 in another etc.” Undoubtably this correspondent’s concerns proved real.

My research has identified many very interesting characters in pharmacy some became identities in their own areas, or further afield. Recently I was given the recipe book for Oddie’s Pharmacy, Timaru (established 1886), which contains hand written or typed formulae for medicines. One such recipe was “Speedy Oil” which had been a well kept secret for years. It was a mixture made up annually for the 1st XV of Timaru Boys High, when they played rugby against Waitaki Boys High. There was a great ritual in applying this performance enhancer prior to the game, and when Oddie’s shop shut, the recipe was divulged to the school, Timaru Boys of course. With the outstanding success of the Crusaders in Supertwelve, maybe this Speedy Oil recipe has been passed through to this best known Cantabarian team.

More on the darker and nefarious side of pharmacy practice have been the reputations of certain pharmacies known for their ability to procure abortions. Alongside this practice was a pill produced by a pharmacy opposite The Town Hall, Auckland and advertised on the shop window as “Retfa Pills.” (“After” spelt backwards.) Used for supposedly preventing a pregnancy “after” the event..

Frank Reed (brother of publisher A.H Reed) was a Whangarei pharmacist that has left his name and memory associated with the extensive world recognized collection of 1st edition books of Alexandre Dumas, donated to the special collections section of the Auckland Public Library.

A major impact that occurred for the main street pharmacies was the arrival of the cut-price Boots Chemists in 1936. Their size and volume can be determined by the fact that in 1955 they employed in their Queen Street, Auckland shop 11 pharmacists in their dispensary and drug department. To quote from a former Boot’s pharmacist from his experiences in the 1950’s. “I received a crash course in dispensing, with rarely any checking of my effort. The unpopularity of Boots in the city pharmacy scene, meant that some other pharmacies would “duck-shove” unwanted, difficult prescriptions to us, and on many occasions found ourselves making batches of pills, individually folded powders, fresh infusions, as well as vast numbers of hand-made capsules and suppositories. We were all equipped for this with Bunsen burner, two pill machines, infusion pot, and even a cachet making contrivance, which I never saw used. Sometimes the equipment would be used for other purposes, such as chocolates made in the suppository/pessary moulds, and our senior apprentice had a recipe for a beautiful liqueur, using now-forgotten ingredients.”

I would like now to mention a natural Disaster of huge magnitude in the industry that occurred on the 6th February 1931. New Zealand has just commemorated the 75th Anniversary of the Hawke’s Bay earthquake. Chemists featured large in the destruction they sustained from the direct effect of the earthquake. However, the damage that emmanated from their premises was greater through the smashing of bottles of inflammable liquids thrown from the shelves, onto the every burning Bunsen burner. These substances quickly ignited and in 3 instances it is known that chemist shops started fires that spread through the area. Pre-earthquake in 1931 there were 7 pharmacies in Napier and 4 pharmacies in Hastings. 6 out of 7 in Napier were destroyed, and all 4 in Hastings were razed to the ground, a massive loss for the area of 10 out of the 11 pharmacies. Gordon Grant pharmacist of Hastings died a few days after the quake from mortal injuries sustained.

To conclude, by the beginning of the post WW2 economic boom, many of the older business practices and traditional shop layouts had given way to more open plan merchandising and dispensing, and the amount of hand making of medicines was very limited. Medicines, equipment and manufacturing supply have come a long way since the 1880 Pharmacy Act. However the pharmacist still interacts and impacts heavily on the community and society with their pharmacy knowledge and street-level health care that was and still is being provided at a high professional level.